An archive with tabs carved in stone

Bottom: chapel and crypts. Right: Régi temetö (the old cemetery, called Spanish). E 15, F 17 and most of B6 are not occupied by graves.

The main cemetery in Timişoara (there is another one, much smaller, non-functional, in the Mehala neighborhood, Aleea Viilor) is bordered by Calea Sever Bocu, former Lipovei, Liniştei street, gardens and the Orthodox cemetery of the poor. It covers 8 hectares, of which 5.3 are covered by graves. In the new and the old cemetery, to the right coming from the entrance, there are about 14,000 graves and 81 crypts.

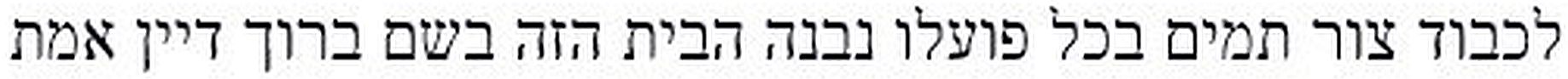

On the frontispiece of the chapel built in the Moorish style practiced at the end of the 19th century is inscribed a verse from a prayer:

This place has been raised to the glory of His deeds, in the blessed name of the true judge.

Inside are three rooms: a large hall, where the funeral ceremony takes place, a vigil room and the mortuary, where the dead are washed. In the great hall, we are drawn to the map of the old cemetery, barely legible, and the spectacular wrought iron chandelier. Next to the chapel is the house of the guard and the caretaker.

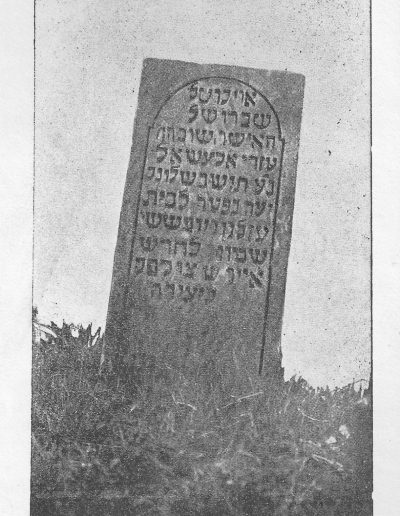

The cemetery is an archive with tabs carved in stone, a valuable documentary support for those who want to know the history of the Jews of Timisoara. The inscriptions document stages in the religious, linguistic and cultural evolution of the community, and the names of prominent personalities attest to its role in the development of the city. If the inscriptions on the ancient stones are exclusively in Hebrew, those of the nineteenth century are often bilingual, in Hebrew and German, the German text being at first on the back, and later making room in front. German will be replaced by Hungarian and, finally, Romanian. We can thus follow the transition of Timişoara from the German to the Hungarian administration, then to the Romanian one, as well as the gradual detachment from the strict observance of the mosaic prescriptions.

On the oldest tomb in the cemetery, that of Assael Azriel from 1636, a Sephardic Jew from Thessaloniki, the inscription became indecipherable, but fortunately the Hebrew text was transcribed at the beginning of the last century. Rabbi Dr. Jakab Singer assumed that he was a rabbi and a doctor, information that is not explicitly mentioned in the text of the inscription.

A place of pilgrimage for Jews and non-Jews is the tomb of Oppenheim or Oppenheimer Zwi (Hirsch) ben David (1793, Almás, Arad County - 1859, Timisoara), a distinguished rabbi and author of biblical exegesis, with the fame of "csodarabbi" (Hungarian), a rabbi who works miracles. The legend has its origins in a story told by Rabbi Dr. Jakab Singer. The Christian guard of the Jewish cemetery, who returned unharmed from the First World War, attributed the survival of the rabbi's posthumous magical power. Thus he became Oppenheimer, who had been sleeping forever for half a century, a miracle-working rabbi in the imagination of many.

Tombstones

The simplicity and uniformity that dominates the Jewish cemeteries are the expression of the will not to transpose the inequalities of life in the place of eternity. Exceptions are the graves of rabbis, the spiritual leaders of the community, with more special tombstones. Due to the prohibition to represent human figures, the stones have a sober appearance, with the inscription as the predominant element, with stylistic variations in the manner of engraving the letters. Towards the end of the 19th century, however, under the influence of the surrounding culture, the social inequality that had existed for millennia, but had spared the cemeteries, also conquered this land. Impressive monuments appear, made of marble or granite, with ornaments in the style of the time and even anthropomorphic images.

Some decorative motifs have a symbolic value, for example, a jug signals a descendant of the tribe of Levi, who had special priestly duties, while a broken branch or a broken trunk represents a sudden and premature death.

Illustrious names evoke the overwhelming contribution of the community not only in the life of Timisoara Jewry, but also in the economic, social and cultural development of the city. Rabbis and community leaders, manufacturers, merchants, writers, artists, journalists, musicians rest with the many, anonymous, who also worked, produced and were useful to society. To the left and right of the entrance are the marble monuments of the great Jewish families, such as Eisenstädter, Gotthilf, Brück, Färber, Hübsch, Rabbi Dr. Jakab Singer. In front of the chapel are buried Rabbi Dr. Ernest Neumann and his wife, Edit, Rabbi Dr. Miksa Drechsler, president of the community between 2004 and 2009, Dr. Paul Costin, and to the right stands the cubist monument of the tomb of Dr. Adolf Vértes, president of the community at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Funeral monument Adolf Vértes, lawyer, president of the Jewish Community of Timişoara, and his wife, Matild

Sources

- Source: Getta Neumann, In the footsteps of the Jewish Timisoara. More than a guide. Brumar Publishing House, 2019